Team Make Mine a Double Goes Back for Seconds at the Great Alabama 650 Paddle Race

By Paul Cox

Disclaimer: The following account contains facts as I remember them. I did my best to double check distances, times, etc. I blame any inaccuracies on sleep deprivation.

Hitting the cold water was a shock. Any sluggishness from more than four days of racing vanished as soon as a wave lifted the outrigger on our tandem canoe, tossing the boat upside down and sending me and Joe into Mobile Bay. We clung to our boat in the night, bobbing up and down in the salty wash, wind gusting above our heads, while I wondered how I — the guy steering our boat — could have let the bay beat us. Less than 30 miles from the finish line, we were facing the biggest setback of the 650-mile race.

Team Make Mine a Double holds the Great Alabama 650 traveling trophy at the finish line. Team members are, from left, Shelly Muhlenkamp, Dee Landau, Joe Mann, Paul Cox and Evelyn Orenbuch. We set a new record of four days, 17 hours and four minutes. Teammate not pictured: Van Bedell

Joe and I couldn’t put a finger on any single reason we decided to race the Great Alabama 650 a second time after setting a speed record on our first attempt in 2020. We had studied our result from last year and were convinced we could cut maybe eight hours from our winning time of five days and 22 hours. Except for a chunk of about four hours before paddling into the city of Selma — which I practically slept through — I couldn’t recall any exceptionally horrible spots. I remember laughing a bunch and, though physically and emotionally drained when crossing the finish line, honestly enjoying the adventure.

But the passage of time tends to replace bad race memories with good ones.

So, Team Make Mine a Double took its place at the race start September 18 on Weiss Lake near the Alabama-Georgia border, already cold and wet as the predicted rain fell hard and wind gusts made it tough for racers to hold their positions at the starting line. We prepared ourselves for five plus days of happy misery.

We chose to start the race in a Huki OC-2, a fast yet stable tandem outrigger canoe modified so we could use either canoe or kayak paddles.

My race partner Joe Mann, a perennial optimist from Kansas City, sat in the front of the OC-2, ready for whatever the next week would bring …

“In the days leading up to the race, a weather system had been swirling around the region, flirting and spitting mostly, but at times dumping rain all across the state of Alabama. The forecast was calling for an 80 to 90 percent chance of rain for the first three days of the race. When we arrived at the starting line, about three hours before race start, it was overcast but the rain held off as all the racers, ground crews and race administration made final preparations. Ultra distance canoe races typically have very anticlimactic starts for spectators; if you are racing for days, you don’t really want to sprint out of the gate. This time, though, it was a bit different.

All the racers entered the water about 15 minutes before the start time, and as we were lined up, with five minutes to go, the clouds that had been doing a marvelous job holding the rain back finally released. This mirrored the pent up energy and excitement of the racers and their crews that was also released as the starting gun went off. Paddles began spinning and pumping through lines of wind that tore across the lake. An unknowing spectator on shore might have thought they could see grimaces on our distant faces, clenched against the assaulting precipitation; they would have been wrong, though. All the planning, preparation and training up to this point was done and a frontal assault from mother nature was the perfect serenade. We were smiling … It was go-time … Let it rain.”

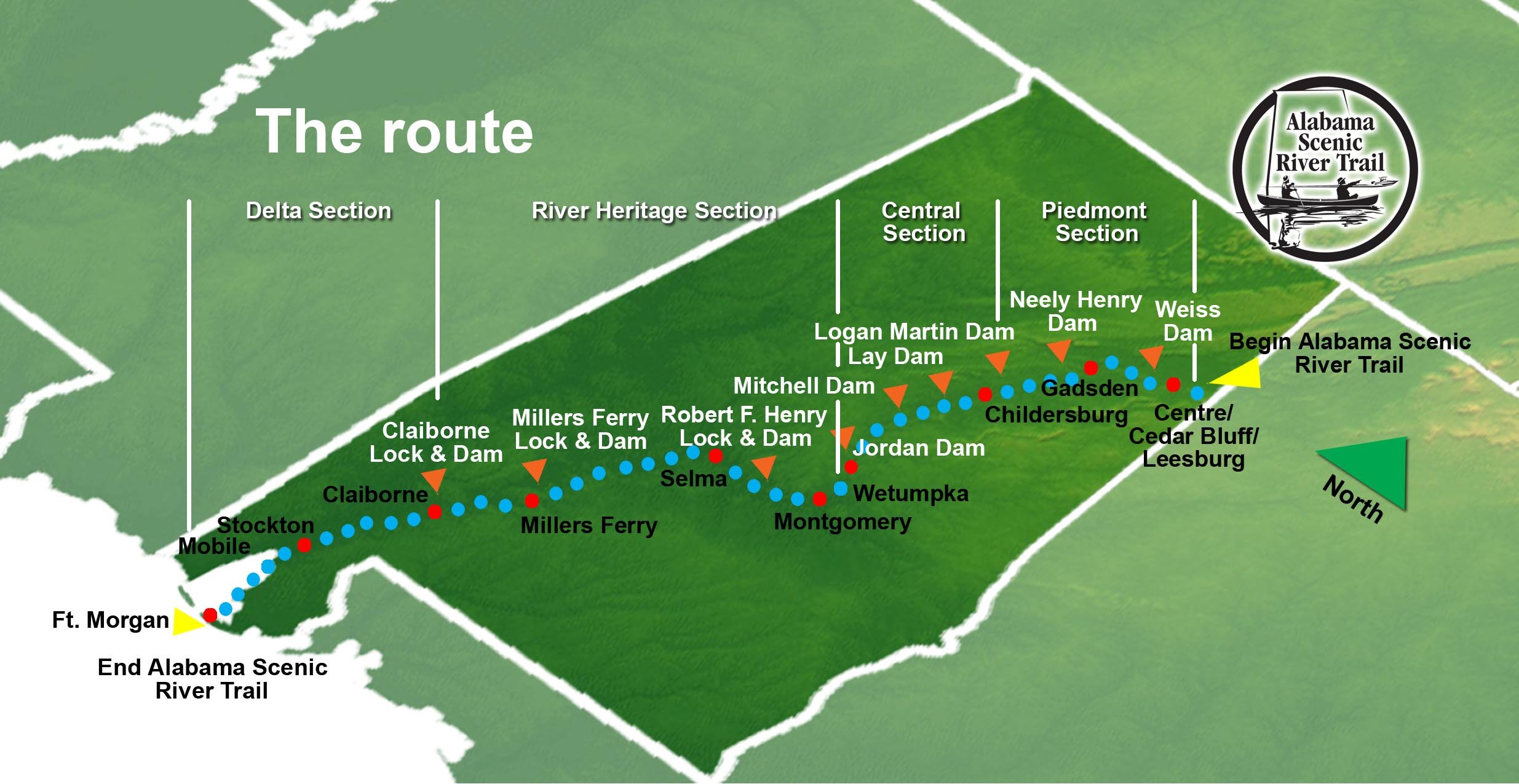

The first eight miles of the race was a straight shot across Weiss Lake to the first of nine portages required to reach the finish line at the Fort Morgan historic site in Mobile Bay.

We jumped out front at the start and, thanks to a lake free of recreational boat traffic, were able to settle into a sustainable pace above seven miles per hour. We were the first team to reach the half-mile Weiss Lake portage, which led to the put-in on the Coosa River. We switched to our fastest but tippiest boat — a 26-foot-long kayak/canoe hybrid that's perfect for waters like the upper Coosa (unlike most paddling races, the Alabama 650 allows racers to use multiple boats).

We would paddle the Coosa across five lakes until the river combines with the Tallapoosa River to form the Alabama River just past the town of Wetumpka, Ala. We’d then paddle the scenic Alabama River as it meanders from the northeast corner of the state, flows west past the state capital of Montgomery and historic Selma, and then turns almost directly south and runs all the way to the Mobile-Tensaw Delta, what Alabamians like to call America’s Amazon.

We knew the Coosa for the roughly 52 miles from the Weiss Lake portage to the riverside town of Gadsden would be at times shallow and winding, with shores densely wooded and full of wildlife including eagles and herons. This remote section could offer a great chance to put some distance on the field if we were the first boat to reach Weiss Dam about 20 miles downriver from the Weiss Lake portage. The current would pick up there.

We slogged through the shallows and then pushed through the upstream flow created by the water pouring in from the dam. But our speed jumped above 9 mph just past the Weiss Dam’s outlet into the Coosa. It was time to dig in until Gadsden.

We’re racers. Joe’s shirt says so.

Providing support for the team’s river adventure was a four-person ground crew. This year’s crew featured two veterans from the 2020 team: my sister-in-law Shelly Muhlenkamp, a West Point grad and physical therapist from Pittsburgh, and paddling buddy Dr. Evelyn Orenbuch, a specialist in veterinary rehab in Atlanta. Joining them was Dee Landau from Kansas City, an experienced kayak racer new to the Alabama 650, and Van Bedell, an extremely good-natured friend of Joe’s from Durham, N.C., who surely would agree later that he had no idea what he was getting himself into. Joe and I can’t thank these four selfless individuals enough for their hard work, ingenuity and flexibility in meeting our every need. Over the next 5 days, they’d pilot three vehicles, including a 24-foot RV, carrying three boats across the entire state of Alabama.

Joe and I had prepared a very detailed, 21-page book of instructions for our crew. In the Race Bible, we’d bundled together every useful bit of race intel we could gather, from locations of local fast food restaurants along the route, to nearby Walmarts, to campground phone numbers and the GPS coordinates of every spot we’d meet the crew to resupply. The first meet-up was an old ferry location, now a boat ramp barely visible from the river and about 37 miles from where Joe and I put in on the Coosa.

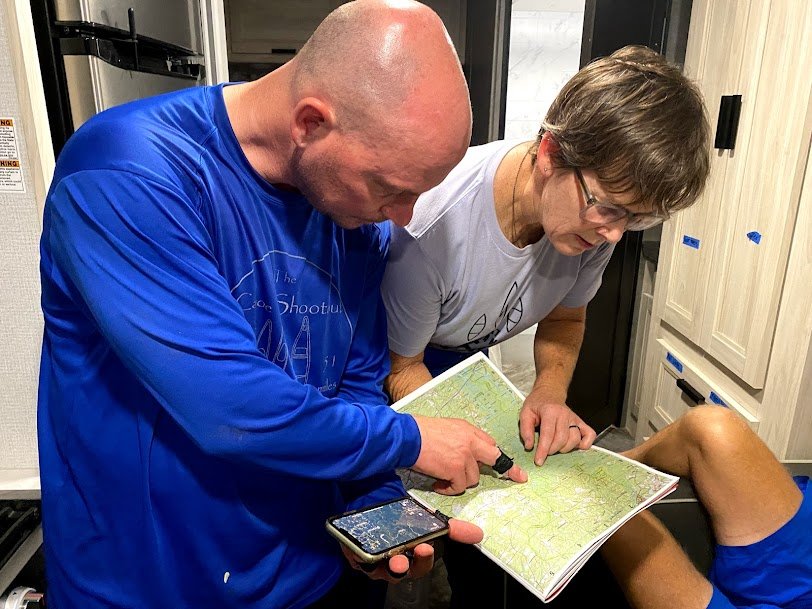

Shelly found a map or two under the seat of the team RV, which she got quite dirty four-wheeling across local baseball fields.

There are plenty of generous souls along the Coosa willing to offer a bit of local knowledge if you just ask — and if the sight of weary racers or ground crew doesn’t scare them away. I can guarantee you’ll be offered a cold beer more than once.

Van recalls the first resupply stop and making new friends there …

“Joe and Paul had launched into the lake at the race start in a pouring rainstorm that began as they were dragging the boat to the ramp. It had continued to rain, hard, ever since.

We (the ground crew) were following backroads searching for GPS coordinates, since the first stop didn’t have an address. Rumor had it that there was an abandoned, derelict ferry boat at the site. We finally found the river, and a secluded, narrow boat ramp, but no ferry. We decided to explore the area a little more to make sure we had found the right place. We drove around in circles for about a half hour and decided to ask some ‘locals’ if we were in the right place — in the pouring rain.

A couple were backing out of their house in a 70’s vintage pickup truck and I got out of an SUV that had two 30 foot boats on top and asked the resident to roll down his window, which he was reluctant to do because, as I said, it was pouring rain.

The man rolled down his window and I saw he had a woman beside him in the passenger seat. He was wearing a cotton plaid western shirt with the sleeves cut off at the armpit. He had many tattoos running down his neck and both arms. The knuckles on the hand draped over the top of the steering wheel said F-U-C-K on them. I estimated him to be mid- to late thirties. They both smiled (a relief) as I asked about the ferry. The woman responded that the ferry had finally sunk years ago and that we were probably in the right place. The man made a comment I wasn’t able to hear over the hammering rain, so I leaned toward the window (none of us wearing masks) and asked him to repeat it. In a southern accent I could barely decipher, he said, ‘Aw, don’t pay me no never mind. I’m a comedian.’ Then he chuckled. I thanked them for their help and the woman said, ‘Sorry but we gotta go. I need to rescue my kids.’ They backed out of the front yard leaving huge red ruts.

We (ground crew) went back to the ramp we had found and decided there was a good chance that the racers could paddle right past us and never even see us or the ramp, so I volunteered to stand at the ramp, in the rain, and signal them as they went past. I could only see a few yards in either direction standing at the water's edge. I tried to drag myself along the bank covered in the slipperiest mud in the universe holding on to branches to keep from falling in. I did anyway, finally standing on an old piling that stuck up out of the river about 12 inches. I stood on it for the better part of an hour, watching the river rise to cover my feet.

The ladies (on the ground crew) had managed to locate our racers’ boat on their cell phones (using the online race tracker) and came out when they thought they were getting close to our location, which was a guess because we couldn't really see where we were in relation to the racers’ location. But, sure enough, here they came and we hurriedly restocked them with water and food. They complained that the wet conditions were already taking a toll on their hands. I thought, ‘great. I’d have quit at the start when it started to rain. Cupla lunatics.’

The three of us on the ground crew slogged up the slope to our vehicles and put in the next set of GPS coordinates. I was shivering in my water saturated ‘rain gear,’ completely soaking the seat I would be living in for the next three days. As our little caravan pulled out, I thought, ‘One hour down, three days to go. I must be out of my addled, senile mind.’ I tried unsuccessfully to reach the bottle of whiskey I had stashed in my backpack.”

Joe and I arrived at Gadsden just before dark and in first place. Our crew fueled us up with food and drink and had our OC-2 staged for the next leg of the race. We wanted the security of an outrigger as we set off into the dark and across the first large lake with no plans to sleep.

Shelly snaps a shot of Van giving us instructions at an early pit stop: Paddle hard. Avoid alligators.

Night 1

Last year, Joe and I didn’t sleep until Selma, though we tried to nap a few times. We actually tried to sleep at about 1 a.m. during the first night of racing, but we ended up just lying in our support van for nearly two hours, our bodies and minds never relaxing enough to allow sleep to come. This year we decided we wouldn’t try to nap until we were too tired to sit upright in the boat.

The first evening of racing usually goes by fairly quickly. The sleep monsters aren’t too difficult to fight off with the help of caffeine and some conversation. Tandem boats likely have an advantage over soloists at night. While there are twice as many paddlers fighting off sleep, it really helps having a partner to talk with, if only to keep each other awake.

The route over the next 155 miles would take us across a series of lakes, including the stunningly beautiful Mitchell Lake with its rocky cliffs and islands. We would portage around the dams on each lake, exchanging boats several times and getting fed and resupplied by our ground crew whenever we met them. There were mandatory downtimes of either 30 or 45 minutes at every lake and river portage, which was never enough time to rest.

Joe and I were thankful the cool temperatures and rain kept the recreational boats off the lakes. There were virtually no boat wakes to contend with, but there was a bitter B-side to the weather -- the wind.

Maybe 20 minutes after Joe and I left our crew at the Adaptive Aquatics Center on Lay Lake, we were hit with an extremely stout headwind and a drenching rain. We paddled hard, as much to generate body heat as to keep ahead of our competition. Still, we may have been barely breaking four miles an hour. I was miserable and just hoped the teams behind us would struggle just as badly when they hit the bad weather. Then a lone watercraft approached us through the bluster.

My inner voice had lots of questions: What was a jet ski doing out in this weather? Why is it plowing through the waves and headwind toward us? Why were the driver and rider pumping their fists in the air? And is that “Eye of the Tiger” blaring from the boombox hoisted atop the rider's shoulder?

It turns out the two on board the jet ski were there FOR US — to inspire us to keep pushing forward. I watched Joe, sitting in front of me in the bow seat, rocking back and forth to the rhythm of the ‘80s hit, clearly high on the vocals of Dave Bickler and the band, Survivor …

“This was without a doubt some of the worst weather I had ever paddled through. Of the 15 times I’ve done the Missouri River 340 and three times I’ve done the Texas Water Safari, usually the unrelenting sun and oppressive heat are Mother Nature’s strongest weapons, and they are horrible to be sure. But, the heat really just affects the paddler, not the craft. This monsoon found a way to inhibit our progress in every conceivable way. The rain soaked us to the bone within minutes, peppering our faces like a shotgun blast. The ferocious headwinds whipped our clothing and threatened to strip our hats from our heads. It threw waves at us and washed them over our deck; it grabbed the tall curved iakos (the aluminum poles that connected our boat to the outrigger). All this caused so much drag, both physically and emotionally, that we had to paddle hard just to keep the boat moving.

Then, after an hour of this madness, I see a jet ski buzzing toward us from across the lake. The jet ski pulled up parallel to us, about 30 feet away, bobbing up and down in the uncertain waves caused by the storm. The passenger in the back held up the boombox, a strange combination – as if John Cusak from ‘Say Anything’ joined Kevin Costner in ‘Waterworld.’ Then I heard the music as the driver took his free hand and began pumping his fist in the air to the rhythm of ‘Eye of the Tiger.’ It took me back to my high school wrestling days as that was one of the songs they always played when we ran into the gym before a match. Oh hell yeah I thought, we got this, and that was all the magic we needed to shut down Mother Nature. In the infamous words of Jennifer Connely in ‘Labyrinth,’ ‘You have no power over me.’ We rocked to that song for another 30 minutes – even though it was only in our heads and hearts — before the storm finally faded away with its tail between its legs.”

The last of the lake crossings ended with the takeout at Jordan Lake Dam, about eight miles upstream from Wetumpka. Just like last year, we arrived at night. And, just like last year, we prepared to run the only whitewater section of the race in the dark.

Night 2

We chose to paddle our ICF canoe — a long, narrow canoe designed to cruise at high speed but definitely not for running whitewater. I’m very comfortable in moving water and have paddled this whitewater section five times previously. Joe had sewn fabric skirts that would velcro across the canoe and keep most of the water out. We expected the two battery-operated pumps mounted in the floor of the canoe could push out any water that got in, and do so fast enough to keep us from sinking. So, I figured our boat choice was a reasonable one.

I would sit in the bow with my single blade canoe paddle so I could hit a brace stroke as needed and steer the bow around any rocks. Joe, steering from the stern, would go with a double bladed kayak paddle and provide the speed we’d need to bust through any holes at the end of the wave trains.

But a huge, ongoing release from Jordan Dam had poured so much water into the Coosa that most of the large rocks and much of the islands in the river were submerged. The usual, predictable wave trains were covered. Instead, we confronted a river full of confused water, swirls and rogue waves that appeared even more random in the narrow beams of our bow-mounted floodlight and my headlamp. To keep the boat upright we’d need to be alert and loose. We couldn’t flip. Rocks downriver would be hard to see in the dark and especially from water level, so there’d be a greater danger of getting raked over the rock islands just below the water’s surface if we went swimming.

We had successfully run about half the length of that section of river to the takeout at Coosa River Adventures — Joe doing a masterful job steering the boat from the stern while I barked out which way to turn to avoid the bigger waves — when a wave popped up from the left. I wasn’t fast enough with a brace stroke on the right. Instantly we were upside down.

Joe remembers nearly getting separated from the boat …

“I saw the wave a split second before Paul. The river pushed us between two huge rocks. We aimed correctly, the rock on our right was 8-10 feet before the rock on our left. Both rocks were under water … perhaps 6 inches, perhaps 6 feet, but either way they caused huge waterfalls. As we dropped into the chute, I felt our bow dive and saw Paul get covered from both sides. I knew at that point we were done.

When you know the boat is going over, the best thing to do is bail immediately, and at the same time don’t get separated from the boat, and DO NOT let go of the paddle!

When I came up for air, the boat had flipped, but thanks to the skirt and flotation bags, it was completely above water (albeit upside down) and had spun 180 degrees. I couldn’t see much in the dark, but I kept hold of the paddle as my other hand grasped for the side of the boat. The rushing water pushed me quickly downriver, my hand sliding without purchase across the gunwale. Finally at the last second, I felt my finger running across the few precious inches of the exposed rudder cable between the boat and the rudder housing. I squeezed it with all the strength I had. It held! I was now holding onto the boat with one knuckle on a 1/16-inch metal wire! I pulled myself with that arm back toward the boat.”

Joe and I called out to each other in the dark and confirmed we both were gripping the canoe and holding on to our paddles. Because most of the rock islands and shoreline were covered with the high water, we decided our best chance to get back in the canoe was to right the boat in the middle of the river, switch on the two battery-operated bilge pumps and then climb back in the boat once it was mostly empty.

After several minutes of floating with our legs up in front of us, ready to take an impact should we collide with any rocks, Joe handed me his paddle and threw himself over the center of the upside down boat, gripping the submerged gunwales on the opposite side, and used his weight to pull the boat back over. Once the canoe was upright, we could see the bilge pumps working, pumping two strong streams of water away from the boat. Joe clambered aboard first, carefully shimmying up the stern then dropping his butt into the stern seat.

Now it was my turn to scramble aboard while Joe kept the boat from flipping as it rocked side-to-side in the swirling water. I was clinging to the bow which now — with Joe seated in the stern — jutted upward several feet above my head. With my paddle in my right hand, I pulled up while flutter-kicking. I then pressed my chest up and above the gunwale, laid myself flat across the bow then, while balancing carefully, twisted my butt over the gunwales and into the seat.

We were back in business and determined not to flip again. We arrived at race Checkpoint 1 – Coosa River Adventures outfitters in Wetumpka in first place – still wet and wide-eyed with what we’d just accomplished in remounting the boat in the middle of such mad water. But, we had a great new story to tell our ground crew.

Joe was quite excited as he was always the one watching our overall time and comparing our progress to last year …

“It was finally at this moment that I allowed myself to acknowledge that we were really doing really well compared to last year. We arrived at Checkpoint 1 in 2020 just as the sun was coming up, perhaps around 6:45 a.m. (almost 46 hours into the race). This year, we arrived right at midnight — 38 hours!. Only 230 miles into the 650 mile race and we were already 8 hours faster than before … more than 15 percent faster! Our goal going into this, though we didn’t say it out loud to anyone other than ourselves, family, and our ground crew, was to beat our previous time by 12-18 hours. However, deep in my heart, I knew that if we ran a great race, we could break the 5 day mark. When we hit Wetumpka at midnight, I began to get excited that we might actually be able to hit that goal.”

Now about 38 hours into the race, Joe and I decided to stay at Checkpoint 1 to sleep for about an hour and a half (and I desperately wanted to brush my teeth) and gear up for the next leg. Six miles downriver from Checkpoint 1, the Coosa River would join the Tallapoosa River to form the Alabama River. The current usually slowed dramatically past Wetumpka. But the release at Jordan Lake Dam and the recent heavy rains meant the usually sluggish Alabama was uncharacteristically swift. Joe and I knew we needed to take advantage of the current while it lasted. Temperatures that night were in the upper 70s and skies were clear. We shifted into night paddling mode, which meant shirts and hats off and single blade canoe paddles out.

I’ve found it hard to have meaningful thoughts during most endurance activities. With mountain biking, for example, you must remain vigilant to avoid a tumble and keep traction. Rocks must be avoided while trail running. But I find long-distance paddling to be different. There’s a singular focus; a rhythm of movement. A sense of humbleness from being alone, or even with a paddling partner, overcomes me in the wide open space of a large river, particularly at night. The mellow sound of the water invites calm.

For me, the evening we left Wetumpka was blissful. If ever I was in the Flow State – or The Zone – this was that time. The moonlight shone just brightly enough to illuminate our way down the river. The breeze cooled us as we dug our canoe paddles into and then pulled them out of the water. I tapped out the rhythm from the bow of the canoe. Every few minutes I closed my eyes and felt for the smoothness that comes when paddlers work in perfect unison. The canoe hit its stride in the current and the miles ticked off in the dark. I stared at the water breaking off the bow and dazzling in the moonlight for minutes at a time. It was mesmerizing. To stay awake and sharp, I played a little “guess our speed” game. I’d clear my head, close my eyes and just enjoy the feeling of the boat gliding down the river. With eyes closed, I’d estimate our boat speed. Then I’d open my eyes and check the digits on my GPS. My estimates were usually accurate within a few tenths of a mile-per-hour.

As dawn broke on a Monday, we cruised silently past Montgomery, the Alabama state capitol, as the city woke up.

Those boys need sunscreen.

Our next long break was scheduled for Selma, about 85 river miles past Montgomery. The Alabama River would widen and we expected it to slow down. The real slog would begin.

The brief nap at Coosa River Adventures had recharged our bodies enough to carry us through to Selma. Last year, Joe and I fought the sleep monsters desperately through the dark for the 29 miles between RF Henry Lock and Selma. This year, we paddled the section in the late afternoon -- very much awake but also looking forward to meeting our crew for a much-needed reboot with a hot meal and a two and a half hour nap. We paddled under the historic Edmund Pettus Bridge and pulled into Selma around 6 p.m.

Shelly and crew cross the Edmund Pettus Bridge into Selma, Ala.

Racing usually prevents teams from spending meaningful time in significant spots along the course. Still, Shelly awaited her visit to Selma with anticipation — no matter how brief the stay would be …

“Of all the stops on the 650 mile race that I was looking forward to the most, it was Selma. It was not because there would be running water or electricity or a variety of food choices available. Selma was not a scenic site; the docking area was under water, and consequently there wasn't a lot of room to park. There were no trees or grass around the dock, no trash cans, and there weren't any nearby grocery stores.

I was looking forward to seeing Selma because of its painful history.

I had seen the movie "Selma" a few years back. ‘Selma’ was first shown in the movie theaters in 2014, directed by Ava DuVernay and written by Paul Webb. It is a movie based on the Sunday, March 7th, 1965 march that began at Brown Chapel AME Church in Selma and proceeded through the town to the Edmund Pettus Bridge. The march was led by Hosea Williams, John Lewis, Albert Turner and Bob Mants. Martin Luther King Jr was in Atlanta, Georgia, at the time. When the peaceful marchers crossed the bridge, they were attacked by the Alabama State Troopers as well as a vigilante band mounted on horses. The Troopers and horsemen attacked the marchers with gas canisters and clubs. Hundreds of non-violent protesters were injured.

The attack on the marchers was caught on film, and helped increase support for voting rights for African Americans. On August 6, 1965, President Lyndon B. Johnson passed the Voting Rights Act. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 expanded the 14th and 15th amendments by banning racial discrimination in voting practices.

With the growing awareness of racial injustices in America (as a middle class, white woman), I wanted to see where the historic march took place.

I likely never would have visited this city if it wasn't for the 650 kayak race. Selma is in a hard-to-reach area of Alabama, off the beaten path, with no nearby beach resorts or beautiful rivers that would bring tourists to the city. Selma doesn't have mansions on the water, private docks or any glitzy tourist attractions. Selma does have the Live Oak Cemetery, listed on the National Register of Historic Places. It is a beautiful southern cemetery, with huge oaks draping Spanish moss over the numerous grave markers. The grave sites are part of Alabama history. But the most notable feature of Selma is the Edmund Pettus Bridge.

I made my way to the dock with the rest of the crew to meet our kayak team. I drove across the bridge as slowly as vehicular traffic would allow, imagining what it must have been like that day in March, 1965. Even though it was 85 degrees and humid, I felt a shiver run through my body. It seemed that the Edmund Pettus Bridge should have been closed to foot and car traffic, with signs posted to alert the passerby to the tragic events that occurred on this bridge. But no, the bridge was open and in use. I wondered how many African Americans living in Selma now had been alive during that fateful march. I wondered if those residents went out of their way to avoid that bridge and its memories. On the other hand, I also wondered if those witnesses to history might intentionally drive across the bridge remembering that they were part of the struggle for the nation as a whole to accept the value and equality of all humans.

I hope that the Edmund Pettus Bridge will be standing for a long time. I hope that it remains as a marker for our country to remember a painful past, yet knowing that the sacrifices of those Selma residents 56 years ago was not in vain.”

Night 3

Fueled up and rested after a three and a half hour stop, Joe and I left Selma in the dark, again with shirts and hats off to keep cool. Alabama has just 5 million total residents. Most live above Selma. For reference, about 5.6 million people live in the metro area of Atlanta, where I live. The stretches between seeing our crew would get longer after Selma, and the river is very remote. Even though we’d rested, Joe and I knew this evening was going to be a tough one. The river at this point was wide, the flow had slowed and it was very shallow at points. There wasn’t a whole lot to keep our minds occupied.

Leaving Selma, now sporting very nice farmer’s tans.

Now, Joe’s a great story teller. He would need to come through with a really, really good yarn to keep me awake between Selma and our next stop 35 miles away, and then the portage at Millers Ferry Lock 35 miles after that. A few hours into this section of the race, as Joe and I were just starting to struggle with the sleepiness that always hits hardest just before dawn, I asked Joe for his best storytelling effort. That’s when he launched into what I’m sure must be the most complete verbal compendium on the history of robotic cleaning machines ever told. He went on for an hour and a half, checking with me about every 20 minutes to make sure I was following along. “I bet you can guess what happens next,” Joe would say to me. I’d offer a mumbled response that I’m sure would have been barely intelligible even to FRESH ears, but Joe continued on.

Why cleaning robots? Joe explains …

“I have spent most of my career in the commercial cleaning industry. I started out as a district manager for a professional janitorial company. Let me tell you, If you need to know how to clean a toilet, I am the guy to call! But all joking aside, I love what I do because I serve my clients. Most people don’t think about how the toilets are cleaned, or how the trash gets emptied, but to make sure a client has a beautiful place to come to work in…that is what I enjoy providing. I have shifted jobs over time and for several years I worked for a company that manufactured professional cleaning robots … Industrial Roombas if you will. In an industry where the most exciting thing is usually 3-ply toilet paper or microfiber cleaning clothes, robots are pretty darn cool. So when Paul asked me to tell him a story, I fell back on explaining the history of professional cleaning robots because I can literally do that with my eyes closed (and still keep paddling).”

Joe’s enthusiastic telling of his robot tale worked. We both managed to keep our paddles in the water until dawn came a few hours before we reached Miller’s Ferry. For me, the 70 miles before Miller’s Ferry was the hardest portion of the race.

Now, unbeknownst to me, Joe and Dee had hatched a plan the previous day to build an outrigger for our fastest boat — the canoe/kayak hybrid — which could be a bit of a handful in the windy, turbulent weather we’d been experiencing since the race started. Joe had given Dee a list of supplies — mostly various lengths and shapes of PVC — that she was to gather from any home improvement store she could find. She delivered the goods at the Miller’s Ferry put-in where, moments after arriving, Joe set about building his erector-set-style outrigger.

Having one expedition paddling race with Joe under my belt, I wasn’t at all put off nor surprised by this impromptu construction project. He promised he could do the job in about 15 minutes. It’s pretty hard to say “no” to somebody so excited about an idea, so I did the only prudent thing a good teammate would do in such a situation — I took a nap. Sometimes it’s best to stay out of the way.

Joe builds his experimental outrigger while I contribute the best way I know how.

About a half-hour later, the outrigger was on the boat (Joe claims the job only took 20 minutes, saying he gave me an extra 10 minutes of beauty sleep). We jumped in the boat and started paddling toward our next stop 47 miles away. Ten minutes later — after it became clear the homemade outrigger was just dragging too much — we decided to remove the outrigger, which Joe did quite forcefully as we were fresh out of screwdrivers.

The experiment was over, but not without a little collateral damage as Joe recalls …

“OK, yeah, yeah…the outrigger wasn’t perfect. What IS perfect with a prototype?!? If I had an extra 20 minutes, and unlimited resources, well … But I knew Paul was doing his best to keep his frustration from boiling over, so I was happy to acquiesce. ‘Out of screwdrivers?’ I think not. But I could sense Paul was no longer in the mood to entertain any shenanigans and time was of the essence. We pulled over, I flipped the boat on its side, and literally RIPPED the PVC pipes off the boat in a matter of seconds. Unfortunately in my boorish haste, as I looked for my iPhone to text the ground crew our location so they could pick up our refuse, I realized that it had fallen out of the boat and I had smashed it during the chaos. There is very little in life that hits you so hard to your soul in today’s age as when your phone is beat and broken. The waterproof case was broken. The screen was broken. The broken phone was in a broken bag floating in water. My life was … ruined? Ugh … first world problems, I know. I did my best not to complain and power on. It was my fault after all because of my silly PVC outrigger idea! And the worst part was that we had used roof flashing tape (imagine gorilla tape + super glue made for roofing) to bind the PVC elbows together. I had to use my teeth to rip it off during the phone-breaking debacle! For the remainder of the race, and several days afterward, I had what tasted like roofing shingle cement in my mouth. I am sure it was very unhealthy, and for the rest of my life, when I smell roofing shingles, I will think of my damned, failed outrigger experiment on the Alabama 650 … but with a smile. :-)”

At this point, the cool weather we’d enjoyed the first half of the race was gone. The afternoon heat was oppressive and it stirred up an afternoon wind storm that belted us in the face. Still in our tippiest boat (without the PVC outrigger), we paddled cautiously to stay upright — a tall order in the heavy wind. When we arrived at Haines Island to meet the crew, we decided — as was our strategy — to grab an hour and a half nap during the warmest part of the day so we’d be fresh to paddle hard at night. After the nap, we had only slept for five and a half hours.

The final portage at Claiborn was only 12 miles away. But the stretches between the next resupply spots would be the longest of the race. Dixie Landing was 44 miles from Claiborn. Cliff’s Landing, our final stop before the 40 mile paddle across the bay, was 54 miles from Dixie.

With about 175 miles left, and a consistent lead of at least five hours over the second-place team, Joe and I could now start allowing ourselves to get excited about the finish. But we had another two nights to get through and the bay loomed. We were determined to finish strong and with a total race time of less than five days.

There were stretches of sleepiness throughout the night, but knowing that every paddle stroke got us closer to Alabama’s delta region and the finish line kept us focused. If one of us started to drift off, we’d launch into some intervals — alternating periods of sprinting and rest. But, what REALLY kept me awake was looking forward to the two to three minutes we each were allotted at the top of every hour to dig into our food stash. I had long ago forsaken the solid “race food” I’d carefully measured into bags before the race and labeled according to each resupply spot. Each bag contained the number of calories I’d need to get me to the next crew meet-up. I’d had my fill of Rice Krispy treats, granola bars and fruit cups. Our meals were now a divinely flavorful concoction of mashed potatoes and some variety of meat product our crew had warmed up for us on the RV stove and served to us Thermoses.

This food break was the only time we allowed ourselves to stop paddling (well, except when nature called). If it was Joe’s turn to eat first, I’d endure his sighs of joy as I paddled in the bow, waiting for him to run out of feeding time. Then once it was my turn, I’d stash my paddle so it wouldn’t fall into the water and I’d reach down to the floor of the canoe and between my feet where I had stashed my Thermos (and where I had jammed pretty much all the necessities for the race). Then as quickly as possible, I’d unscrew the top of my Thermos and dig my fork into the goodness inside. The nourishment was always warm. Always good. This routine went on for most of the evening. Then the unthinkable happened.

Joe had just finished his brief feast and gave me the go-ahead to dig in. I reached down for my Thermos. It wasn’t there. My free hand frantically searched, first in front of my seat, then I twisted around toward the stern of the boat enough to thrust my hand behind me and rustle under and around my jugs of water and my PFD. All in vain. No Thermos! Where was my Thermos?!? Joe would later tell me how impressed he was at the amount of contorting going on in the bow of our tippy canoe, all in the hunt for my precious Thermos. Finally, I located it. It had rolled under my seat and somehow had become hopelessly trapped under the aluminum rails that held my seat to the canoe. I tugged at it to no avail. I was devastated. My inspiration was less than an arm’s length away, but I couldn’t free the Thermos from its confines no matter what I tried. After the race, Shelly asked me why I hadn’t eaten my meal. She had assumed I didn’t like her cooking. How wrong she was.

We were in great hands with Dee, Evelyn and Shelly as our crew! Not pictured: Van, who wisely had something better to do.

Night 4

Joe and I pulled into Dixie Landing ready to stretch our legs for a bit and refuel for the longest stretch between meet-ups with our crew. As always, Dee, Shelly and Evelyn (who had tagged in for Van as his replacement a day earlier) were ready and waiting for us. But they had just enjoyed an adventure of their own, as recounted by Dee …

“The Make Mine a Double ground crew portaged our guys at Claiborn and headed off in search of gas for the circus vehicles on our way to Dixie Landing. We hit a small town shortly after midnight and didn’t have much hope of finding anything open. The second place we found said “open” in the window but the lights were off at the gas pumps. We pulled in anyway and gave it a try. The gas pump accepted the credit card so I went inside to talk to the cashier. He asked who we were and why three drunk-looking women were out wandering the town at midnight and when we told him about the race and what we were doing, he turned the lights back on over the gas pumps so we wouldn’t have to pump in the dark. We filled the three tanks and attracted two or three other customers into the store, so I think even though he had to stay open later than he wanted, he made more money thanks to us, so we made his night!

Driving back roads between midnight and 6 a.m. is always an adventure and tonight gave us an entire family of raccoons to dodge. Evelyn was leading and thankfully the other two vehicles were behind at a safe distance, because there was heavy braking involved to preserve the lives of all the raccoon kids … phew!

Dixie Landing Road is basically a dead end on a cliff. We parked the traveling circus and I grabbed the Luci lights to put out as welcome beacons for our team to see when they came around the bend. While scanning the cliff to search for the best landing spot, I was greeted with the glowing eyes of a gator in my flashlight beam. He/she was not happy to be spotted and went under with a large splash. Thankfully, the high water had lessened the cliff climbing and we had a relatively easy spot beside a fishing boat where the guys could land and then just walk up a short steep section to the road.

I got a text from Barbara (sister of racer West Hansen and part of his ground crew) around 3 a.m. asking me where we were. I pondered the moral dilemma of this before answering her. I didn’t want to give out intel to our competition, but West, Barbara and I have been friends for over 15 years and it just didn’t seem right to not answer. So I texted back and told her where we were and how many river miles it was from the last portage. When Joe and Paul arrived, I told Joe that she had texted and he responded, ‘Did you tell her?!?’ I said ‘of course I did’ and he said ‘I would have too.’ Oh good … thought I might have gotten fired and sent packing, but all was well!

The stop was fairly short for the guys. We fed them, got their resupply ready and Paul contorted himself into the corner cushion, basically under the kitchen table to have a quick upside-down nap while Joe double checked the maps for the next leg.

After we sent them off, we decided we had time for a nap there on the quiet dead-end road before we needed to move on, so the three of us crashed for an hour or so, then took goofy group selfies with the RV and struck off for Cliff’s Landing.”

I’ve competed in multi-day endurance events for about 20 years. Over that time I must have developed some sort of weird conditioning to quick naps that makes a five minute sleep work like a full-body recharge. At least that’s what my brain tells me. During a long race, even a few minutes relaxing with eyes closed is time well spent. That five minute nap at Dixie Landing was good enough to get my body back in the boat and ready to go harder on the final section of river before it met the bay.

Hey Joe, we paddle downriver.

Don’t mind me. I can fall asleep anywhere.

The water was again moving quickly due to the huge amount of recent rain and the blessing of fast water continued all the way to the delta. Joe and I kept our brains engaged and our speeds up by linking up lines of swift current around the bends as the river wandered southward. Still in the ICF canoe and paddling with our single blade canoe paddles, we hit some of our highest speeds of the race on this section, topping 11 miles per hour. I felt as fresh as I did on day one. We were flying and it felt wonderful.

Apart from Mitchell Lake, this was my favorite section of the course, particularly when our route took us on a quick jog through the tropical Tensaw River and Bottle Creek — which is chock full of gators. It was this section of river that provided the most excitement in last year’s race. On the last warm afternoon of the race, Joe and I surprised a huge napping gator when we paddled directly over it. The gator jumped and so did Joe … nearly completely out of the canoe. I thanked the gator — and Joe — for the entertainment and kept paddling.

Our three-vehicle traveling circus at Cliff’s Landing.

Our stop at Cliff’s Landing was brief — just enough to change clothes, catch our breath, get some food and switch to our OC-2 that would deliver us across the bay. We set off for our next stop just past Mullet Point about 32 miles away. We had a five to six hour lead and we felt sure we’d be able to finish in under five days when mandatory portage time was subtracted from the official finish time. Still, the paddle on Mobile Bay was the most difficult and unpredictable section of the race.

Joe gets help applying the lotion at Cliff’s Landing.

My idea of using time wisely.

The weather forecast for the bay called for winds from the north, which meant we should get a nice push as we traveled south into the bay and then 30 miles along the eastern edge of the bay before rounding a buoy in the southeastern corner of the bay and turning west toward the finish line about 18 miles farther at Fort Morgan.

We’re missing someone! Hey Joe, are you done applying the lotion?

Night 5

The afternoon was coming to a close as we paddled past Spanish Fort, Ala., and darkness fell by the time we entered the open water beyond US Highway 10. Race rules required us to follow a GPS track for the entire race. This track, which appeared as a pink line on our GPS units, would keep us within a couple hundred yards of the shore and in water only about 3 feet deep for the first several miles after entering Mobile Bay.

Off we go from Cliff’s Landing on the last leg of the race. The bay crossing loomed.

Waves grow when they run from deep to shallow water, so the bay was a washing machine of waves that seemed to grow out of nowhere. I sat in the stern of the OC-2 and was in charge of the rudder controls. I kept looking over my shoulder for some rhythm to the waves so we could take advantage of the surf. We caught a ride on a few waves, but it never lasted long in the chop. I steered the boat a bit further from the shore and then back in, looking for more peaceful water. I never found it. Still, Joe and I were making good progress across the bay at night, leaning into the outrigger to keep the boat stable. Then we were upside down.

I was more shocked than anything when we flipped. The boat would be easy to remount, but had we lost any gear? Where was Joe? How could I have let this happen? And how many more times would we flip? Joe swam over to the boat and we remounted quickly. Nothing too valuable was lost. But now wet, we started to chill quickly and we were still in the midst of a real tumult. We needed a reset of mind and body.

The overturning of the OC-2 marked a first for Joe …

“In all my years in ultra distance racing, I’ve only fallen out of the boat a handful of times and never has it happened twice in the same race … until now. First at the rapids near Wetumpka, and now here in the bay. I hate bays. Let me say that again: I F’ing HATE bays. Like Paul said, they are a washing machine of water. I thought the bay in the Texas Water Safari was bad, and that was only 5 miles. This is 50!

We hit the bay, 50 miles to the finish, at approximately four days and change or right around 100 hours into the race. If we could finish in 20 hours or less, we would crack the five day mark — my goal for this endeavor. This should be easy to do on paper, but again, I knew what was waiting for us. I knew that bays were relentless and unpredictable. On top of that, a windstorm had blown in. 20 mph winds with gusts up to 30 challenged us. Just as Mother Nature hurled herself at us at the beginning of the race with the rain and wind, in the middle of the race when we persevered thanks to our still unknown friends on the jet-ski blaring “Eye of the Tiger”, she had now saved all she had for the finish.

Reverberating waves were coming at us from all angles, and somehow — perhaps it was the exhaustion — or most likely the combination of that and the winds, the most stable boat in our arsenal was upheaved. We were in the drink. I quickly scanned the situation. Paul, as any good paddler had his paddle in one hand, and had the boat gripped by the other. ut both of our liquid bladders, our seat cushions, and the only dry bag we had filled with food and first aid were all floating haphazardly far from the boat. I made a quick decision that I should try to save all of this. It took a lot of effort and a lot of swimming. Each time I grabbed something valuable, I would tuck it in under my left arm, and swim to the next item. By the time I had all of it, my neoprene boots were sliding off my feet so that I had to clench my toes to keep them from sliding off. I basically had to swim back to the boat with one arm, no legs, while holding two bladders, two seat cushions, and a dry bag under my left arm, while Paul flutter-kicked the boat toward me.

What felt like hours was really only five minutes, but the exhaustion hit me. We had to get to shore and recharge.”

I angled the boat toward the shore, hoping we’d at least be close to the beach if we flipped again. The GPS track mandated that we head toward the shore and Fairhope Pier, where we saw a cheering and ALWAYS upbeat Mike Malone from racer Salli O'Donnell's crew. We nearly slammed into a pier support as the waves lifted and twisted the OC-2, and had to throw ourselves on the outrigger to keep from flipping again. That’s when we decided we’d make an early stop to see our crew. Rather than paddling around Point Clear and into the sheltered water at Mullet Point four miles further, we pulled over at a very welcoming beach in Fairhope, Ala., and called our crew to come meet us. We needed some food, sleep and some TLC. Of course our crew answered the call. We also let race director Greg Wingo know he’d likely see our position in the GPS tracker stay in one spot for a while and also to report that the water in the bay was pretty mean that night. He told us a Small Craft Advisory had been issued. Hearing that, I felt a bit better about the decision to pull over.

This is how Evelyn remembers the stop …

“It was definitely a bit different of a stop. I was napping, Shelly and Dee were taking pictures of the sunset (having not woken me to see it …) and we were settling in for a relaxed evening of organization and preparation (Shelly's favorite pastime) when suddenly … like a thief in the night, a thin voice of desperation on the end of the phone stole away our plans … and off we went. First Dee, then me, then Shelly as we packed up and prepared for the worst.

Fortunately, our nightmares were not realized. Our racers were haggard, wet, cold and annoyed. But, they had come to terms with the situation and were well into the planning stages. With Joe barking out the minute by minute plan for the next four hours of our lives, we ran around filling each need — a place to sit, dry off, warm up, quench the thirst and hunger — all while I quietly thought to myself … Hmmm … If they had only listened.

I had suggested they stop just a bit above this spot, but my suggestions had been quickly dismissed out of hand so that they could push on beyond normal human limits to the bottom of the bay without a stop. But then again, these two were not normal humans. Who could blame them?”

What stuck out to Dee? Our fashion choices …

“ ‘We’ve had an accident’ is never the first sentence you want to hear when you answer your phone. Thankfully this was likely not Joe’s first accident that he needed to call and tell someone about, so he knew enough to start with ‘we are okay,’ and (because it was integral to the race) “the boat is okay” but they had indeed had an accident at sea and were washed up on a beach up the coast from us and needed our help.

We had just had a quick nap at a beautiful spot down the coast from the point that the guys wanted to get past before stopping. We enjoyed the sunset and Shelly had started prepping food when the distress call came in. Joe dropped me a pin of their location and I hopped in the van and headed off to find them. Evelyn started to come as well in her car but we decided she should go back and wait for the food to be ready and then bring Shelly with her in her car. We left the RV there for the time being.

I drove past the guys sitting wet and cold on a park bench and pulled into a parking lot just 50 yards or so from where they were sitting. My phone rang again. Joe said ‘we are down here on a bench’ I replied ‘I saw you there, but I can’t drive the van down the sidewalk, I’ll need you to come to me.’ I got a sad sounding ‘okay’ as my reply.

The guys were soaking wet and starting to get chilled so I instructed them to get all their wet clothes off and put on the long Surf-Fur Water Parkas I had brought for just such an occasion as this. It’s important to note here that when I told the guys I was bringing them, Joe Mann scoffed at that and said it wouldn't be that cold and there would not be a need for them … he was singing a different tune as soon as he put his on!

Shelly and Evelyn were not far behind with hot food but, as we waited, the guys found great humor in wearing only long black parkas and standing beside a van with two twin bed mattresses inside. ‘We must look like perverts…’ was mumbled more than once.

Warm and fed, the guys crawled into the van to sleep for three hours. The ground crew moved the RV up to this location and hung their wet clothes up in the ocean breeze to dry. Then we went down the beach to find the boat and assess what needed to be done there. The tide was coming in so we moved her up the sand above the high tide mark and made sure all the gear was still aboard and secure. We tried as often as we could to sleep when our team slept and getting three hours all in one stretch seemed like a luxury so we all piled into the RV to grab some sleep. Two hours later, I heard a hoarse whisper of ‘hello’ from outside the RV door and Joe was up and ready to get back out there! Turns out the hoarse whisper wasn't just his way of gently waking me up, it was all the voice he had left and it took all my concentration to understand him as we talked while getting him geared up for the last push of the race.

The guys layered up with wind/rain jackets on their bodies and winter hats on their heads. To help retain heat, we tore an emergency blanket in half and wrapped Joe’s legs then secured the mylar with his race tights. The silver shimmer through the tights was quite fancy! Shelly shared her water shoes with Paul to help keep his feet warm and they just happened to be his shade of pink! Team MMAD was styling!!

With the guys bundled against the elements, we all trudged back down the beach to the boat, loaded them up and shoved them off into the pounding waves. I waded to my waist in the ocean to help get them settled and shove them off and was relieved to know that the water was at least warm, even though the air was chilly.”

The unplanned stop at Fairhope had turned into a four-hour layover, though it could have been a bit longer if Joe hadn’t noticed the competition was gaining on us …

“After we had warmed up and eaten, we laid down in the van to sleep. I looked at the tracker and saw that the second place team was five hours behind us. I set the alarm for three hours. I woke up naturally two hours later and looked at the race tracker (on the phone). The other team must have seen us stop on the tracker and was mounting a full court press. They were only six miles away! I woke Paul up, apologized for the early wake up call and explained the situation, knowing that it would take us at least 30 minutes to get up, get dressed, get our gear ready and get back on the water. Of course Paul jumped to life.”

When it came time to get back in the boat, Joe and I were recharged and ready to hit it hard. Launching from the beach and then turning left in the heavy surf would be a bit tricky, but neither Joe nor I flinched. It was time to crank out the miles and finish things as we knew the second place team of Bobby Johnson and Rod Price was on our heels. I turned the boat south, the OC-2 taking a beating in the waves as it changed direction, then steered toward Point Clear.

Once around the point, the bay turned face — the water now docile. There weren’t any waves to surf, but we could at least relax, eat a bit and concentrate on covering miles. With winds still coming predominantly from the north, we knew we’d once again have to deal with the bay’s bad attitude when we turned west after passing Checkpoint 3, where the Bon Secour River dumped into the bay.

It was an extremely rough 18 miles to the finish. The stern of the OC-2 rocked up and down like a mechanical bull turned to 11, and nearly five days of paddling had left me with an extremely painful backside — like how it must feel paddling with 30-grit sandpaper clinched between my butt cheeks. But, Joe and I were finally in a groove. I had figured out the rhythm of the short, choppy waves. I feathered the rudder pedals back and forth as the boat lifted up on the crest of a wave, accelerated for a few moments, then dropped down into the short troughs. I kept the boat on the GPS track, which made a bee-line to the finish rather than hugging the contour of the shoreline.

Joe — again, not a fan of bay crossings — even enjoyed the final push to the finish line …

“Although I HATE bays, somehow Paul and I did in fact find our groove here. What I expected to be the worst part of the water, and what was definitely the most treacherous, ended up being the most fun. Paul did an incredible job steering, and I was able to do a good job balancing power and stability in heavy swells … for eight plus hours. Getting back in that boat from the parking lot in the middle of the night, during a Small Craft Advisory, was probably the mentally toughest thing I have ever made myself do. Our heads were on a swivel, and our ground crew even made a surprise appearance a dozen miles later in order to bring us more water and snacks. Our competition must have seen us moving, and realized that they couldn’t contend. They ended up stopping for several hours very near the same parking lot as we had.”

Dawn arrived and the finish line came into view. A few hours afterward we rounded the pier at Fort Morgan and paddled into the fort’s boat slip, bouncing along with the wind-driven surf that had never relented.

Watch: The finish!

Our finish time — adjusted to subtract the required portage time — was a new course record of 4 days, 17 hours and 4 minutes. We’d achieved our goal of finishing in less than 5 days and had beaten our previous course record by more than a day, thanks to a very capable ground crew, a year of experience under our belts, better planning and rivers full from recent rain. We slept about eight hours total during the race, give or take a few of my five-minute naps.

Great Alabama 650 Race Director Greg Wingo congratulates me and Joe on the win at the finish line.

The second-place team of Bobby Johnson and Rod Price crossed the finish line more than five hours later with a time of four days, 22 hours and 25 minutes. Salli O’Donnell won the solo female division for the third year in a row with a finish time of four days, 22 hours and 39 minutes. West Hansen set a new solo male record with a finish time of five days, 19 hours and 9 minutes.

Shelly with my mom and dad, who surprised us along the race course.

My dad is always at the finish line, wherever it is.

Thanks so much to our amazing ground crew, my parents who surprised us with a visit at two spots on the course including the finish line, Allen McAdams and Melanie Hof for loaning us the OC-2, the folks from Alabama who cheered for us along the route, and of course Greg Wingo and all the amazing race volunteers. And thanks to RPC3 for the kayak paddles, ZRE for the canoe paddles, and Hammer Nutrition for all the race fuel, water bottles and really cool hats.

Mobile Bay, in calmer moments.